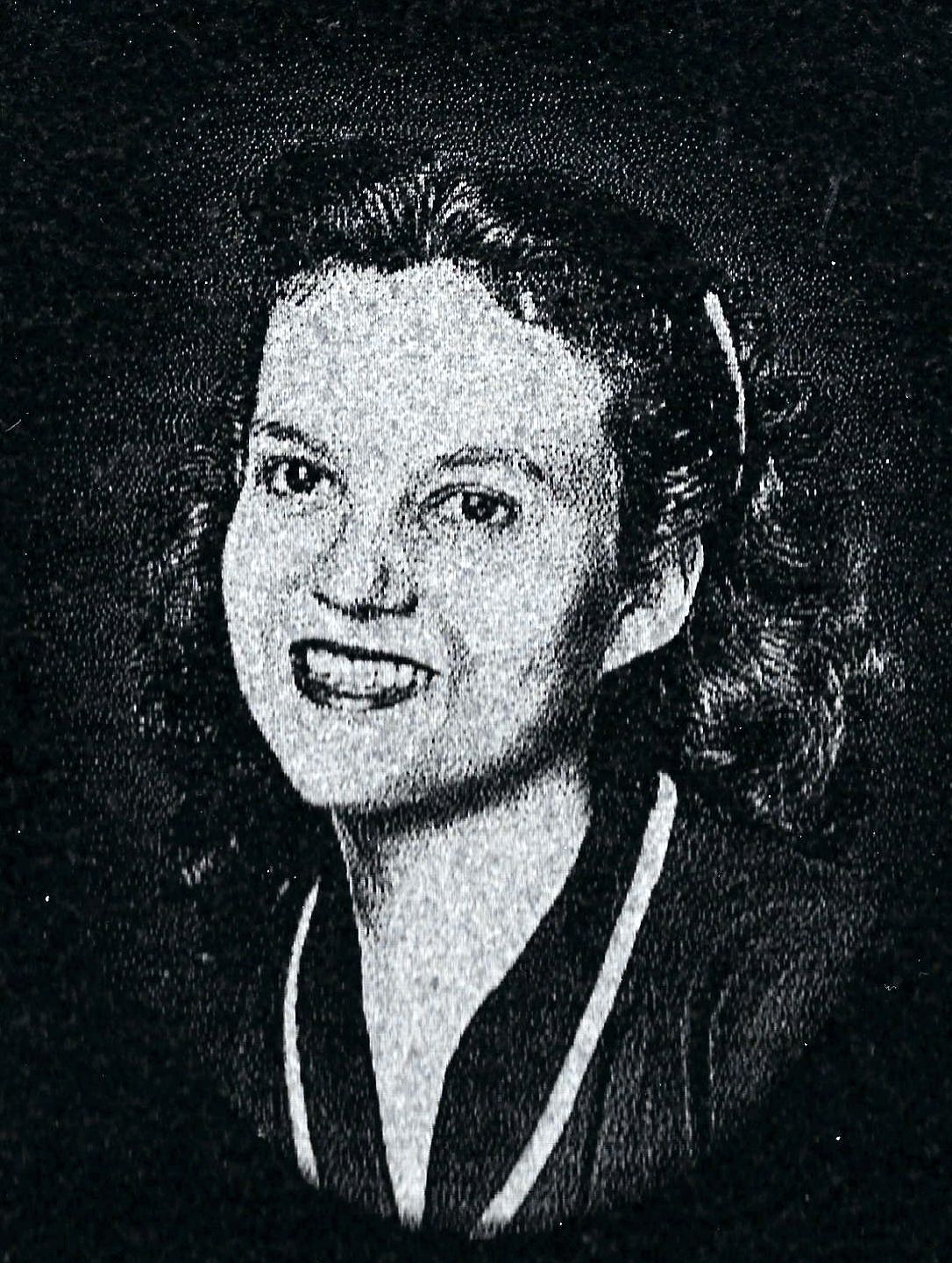

Carving Memories for

Generations to Come!

Custom Memorials

Classic Designs

Landscape Boulders

Sculptures

Mausoleums

Columbaria

Civic Memorials

Final Date Lettering

About Young & Company

Young and Company was established in 2010. Scott Young, owner, has had a passion for memorials for many years that has overflowed into his team members. With over 25 years of combined experience, the Young & Company team is dedicated and focused on quality and satisfaction for memorials that will withstand the test of time.

Our Team

The Young & Company team is a select group of individuals that are skilled craftsmen in this trade. With years of experience, Scott Young and the team, stand behind the quality of their monuments because of the time and attention that is put into each one. Let us help you create the perfect stone for you and your loved ones.

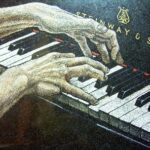

Our Latest Projects

The Young & Company team constantly have something new in the works so be sure to stay updated with us here or on one of our social media platforms. New projects and products will be displayed frequently.